Is Amazon ‘shadowbanning’ sellers and deceiving Australian consumers during Prime Day?

This week, from the 16-21 July is Prime ‘Day’, where many consumers are enticed to Amazon’s marketplace for great deals. But our researchers noticed something strange in Amazon's search results and its algorithmic recommendations: sometimes, cheaper items that ship faster are invisible in searches, and the 'Amazon recommends' offer is nearly twice as expensive as the best deal! It's not clear what's happening here, but legally, Amazon could be in trouble under Australian consumer law.

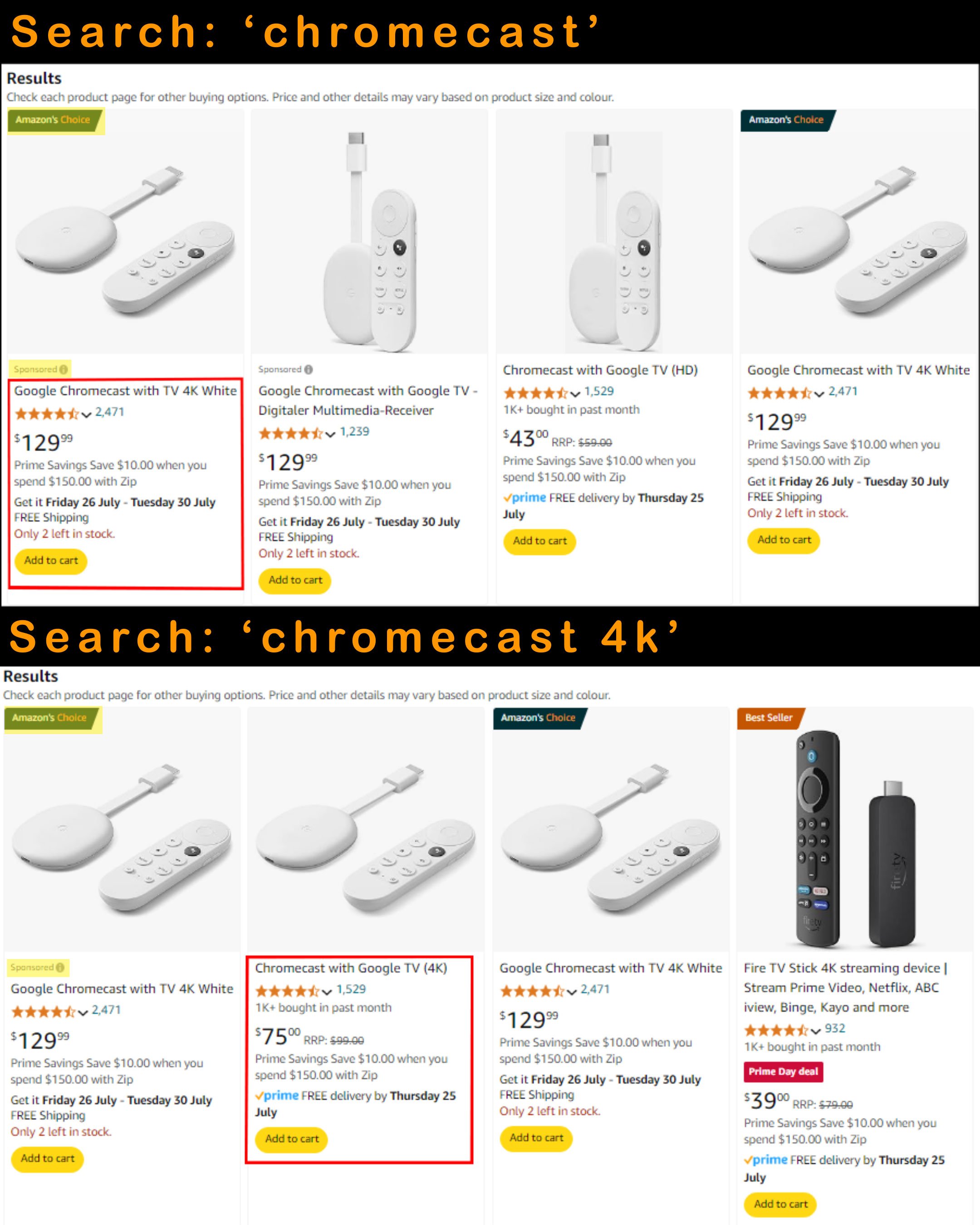

Amazon highlights products as ‘Amazon’s Choice’ according to ‘what customers tell us matters most to them, including ratings, price, popularity, product availability and fast delivery’.[1] If you search for ‘Chromecast’ on Amazon’s marketplace, the ‘Amazon’s Choice’ recommendation to consumers is the ‘Google Chromecast with TV 4K White’ from a third-party seller called ‘Daily Deals’. The listing is at $129.99 and is not available for prime shipping. In contrast, if you search for ‘Chromecast 4K’, the ‘Amazon’s Choice’ recommended product is the same listing from Daily Deals, but the search now provides an listing from the official Google Amazon store priced at $75.00 and this listing is available for prime shipping. If you run the first ‘Chromecast’ product search, the official Google listing is omitted from the search results.

This appears to be a case of the recommendation algorithm potentially misleading consumers.[2] The use of the ‘Amazon’s Choice’ label on a significantly more expensive listing of the Chromecast 4K that does not offer fast shipping and the omission of the Google listing from ‘Chromecast’ search results could be misleading or deceptive conduct under cl 18 of the Australian Consumer Law. The express representation that the third-party listing was ‘Amazon’s Choice’ is likely capable of leading consumers into making a purchase from the third party seller, and this could be an error made in reliance of that representation because there was a cheaper listing that was omitted from the search.[3] The conduct may be found to be more than just fostering confusion [4] – it could involve a real possibility of misleading or deceiving consumers to purchase a more expensive product without effectively informing them that there is a cheaper listing.[5] The ACCC have taken action in cases about search results before, and as a result companies had to be more explicit that they ranked search results for their own profits. But companies are not prohibited from the practice itself. The ACCC is currently targeting these kind of representations in search results.[6]

The behaviour of Amazon could additionally raise competition issues. However, to prove ‘misuse of market power’, you would also need to establish that Amazon had ‘substantial market power’ and this is a high threshold.[7] Amazon competes with a variety of other retailers for technology products, which may mean that it does not have ‘substantial market power’ in this market segment.

This looks like a worrying example of the hidden choices and values that make up search results and recommendations that consumers rely on every day. At the ADM+S, our researchers study the social impact of automated search, curation, and recommendation systems. Australia is currently working to develop new regulations for the development and use of AI. Australian law already includes robust protections for consumers; the next challenge is making sure that we are able to monitor concerning issues as they arise and ensuring that existing laws can be enforced to protect consumers.

Thank you to Prof Nic Suzor for their advice and assistance with this post.

Notes:

[1] ‘Amazon’s Choice - Frequently Asked Questions’, Amazon (Web Page) <https://www.amazon.com/b?ie=UTF8&node=21449952011>.

[2] For ongoing research on recommendation algorithms, see ‘Considerate and Accurate Multi-Party Recommender Systems for Constrained Resources’, ADM+S (Web Page) <https://www.admscentre.org.au/considerate-and-accurate-multi-party-recommender-systems-for-constrained-resources/>.

[3] Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (2013) 249 CLR 435, [92].

[4] Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (2013) 249 CLR 435, [8].

[5] See Tillmanns Butcheries Pty Ltd v Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union (1979) 42 FLR 331, 346.

[6] ‘ACCC to Examine Internet Search’, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (Web Page, 18 March 2024) <https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/accc-to-examine-internet-search>.

[7] See s 46(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); see also Queensland Wire Industries Pty Ltd v Broken Hill Pty Co Ltd (1989) 167 CLR 177, 187–188; for commentary on competition law and Amazon, see Lina M Khan, ‘Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox’ (2017) 126 Yale Law Journal 710, 710.